The Wigam Collection

The word vision has several meanings: it is the way how we look and see things, but also how we construct and envision the reality. In this exhibition these two concepts intermingle, since good art forces us to become aware of the process of seeing – that is not objective nor innocent – and shows us at the same time how we construct our lives and by doing so, what matters to us.

During the last decades we have been exposed to big social, political, and cultural shifts in the world. Art is a perfect vehicle to reflect on these shifts since nothing expresses ideas, hopes and fears of each particular time better than an art object. Sometimes, art can give us unexpected insights and push us out from our comfort zone. Sometimes, it simply overwhelms us with beauty and clarity.

This exhibition that presents works coming exclusively from the Wigam Collection, is centered around two main visions of the world: in the first space the focus lies on the experience of the world through the body, while in the other the world is firstly and foremostly observed and lived through the social interdependencies. Needless to say, this distinction signals only the primary point of attention since one cannot think about the body without its social habitus and conversely, the social order is personal and physical. These two visions, reflected in outstanding works made by some most interesting artists of our time, seem to be of great relevance at this moment.

BODY

PART I

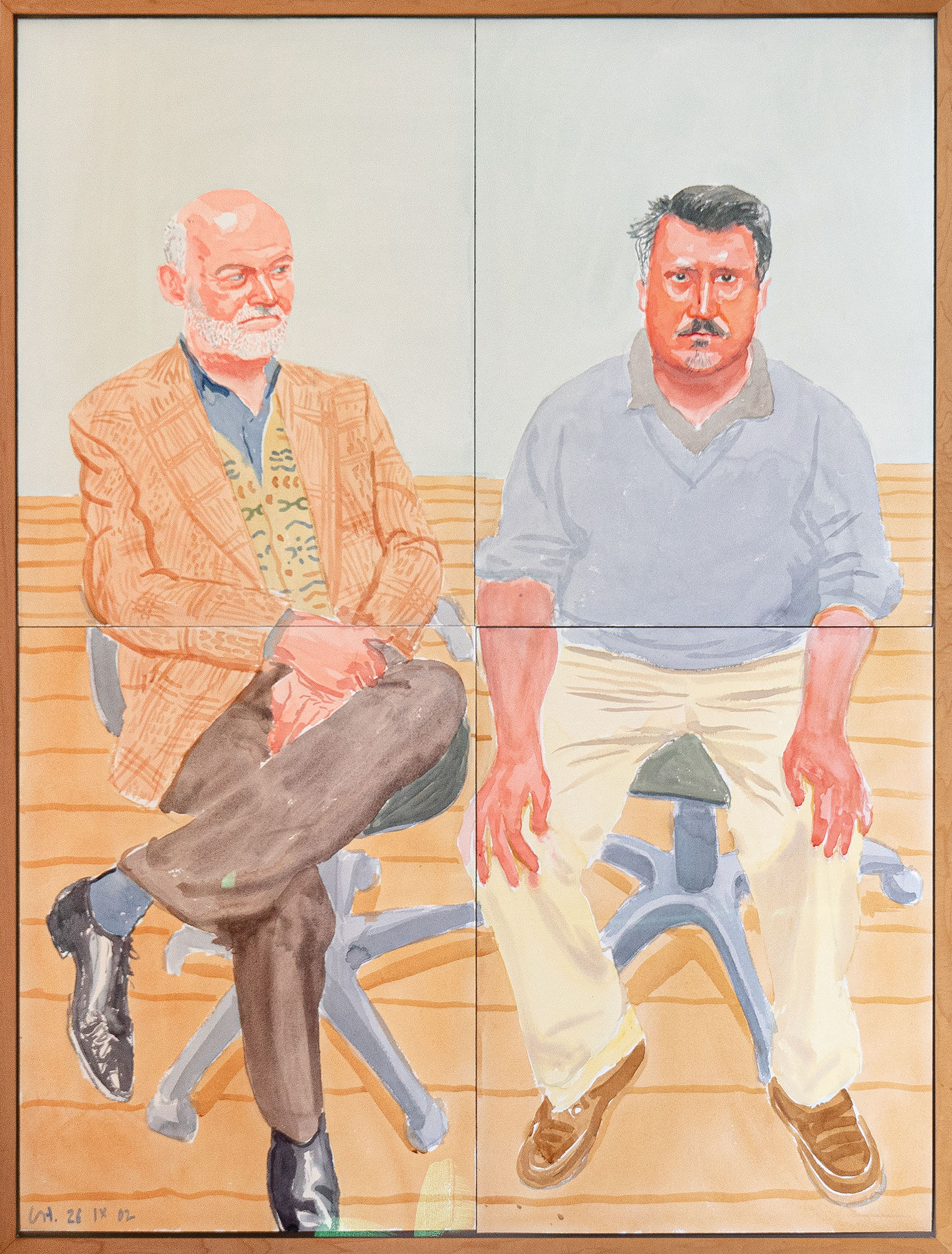

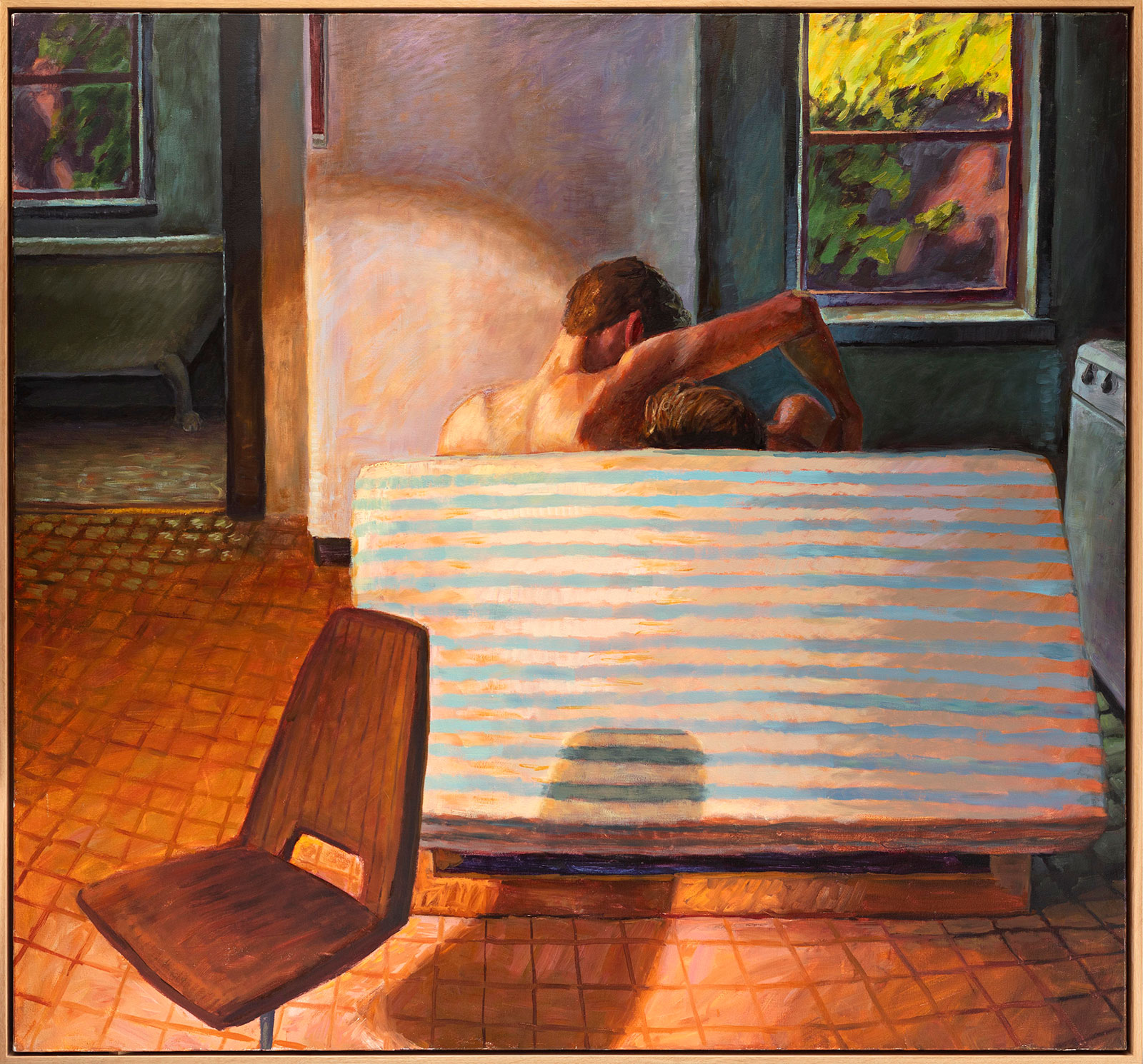

Section one revolves around the idea of the body expressed in the works by LGBTQ artists. The portraits made by the young and celebrated American artists Anthony Cudahy and Louis Fratino depict their lovers and friends enjoying their daily lives – eating, having sex, meeting family – in the same way David Hockney earlier portrayed subjects causally seated and talking. These paintings implicitly express a strong longing for normality of the queer existence, and for its acceptance by society at large.

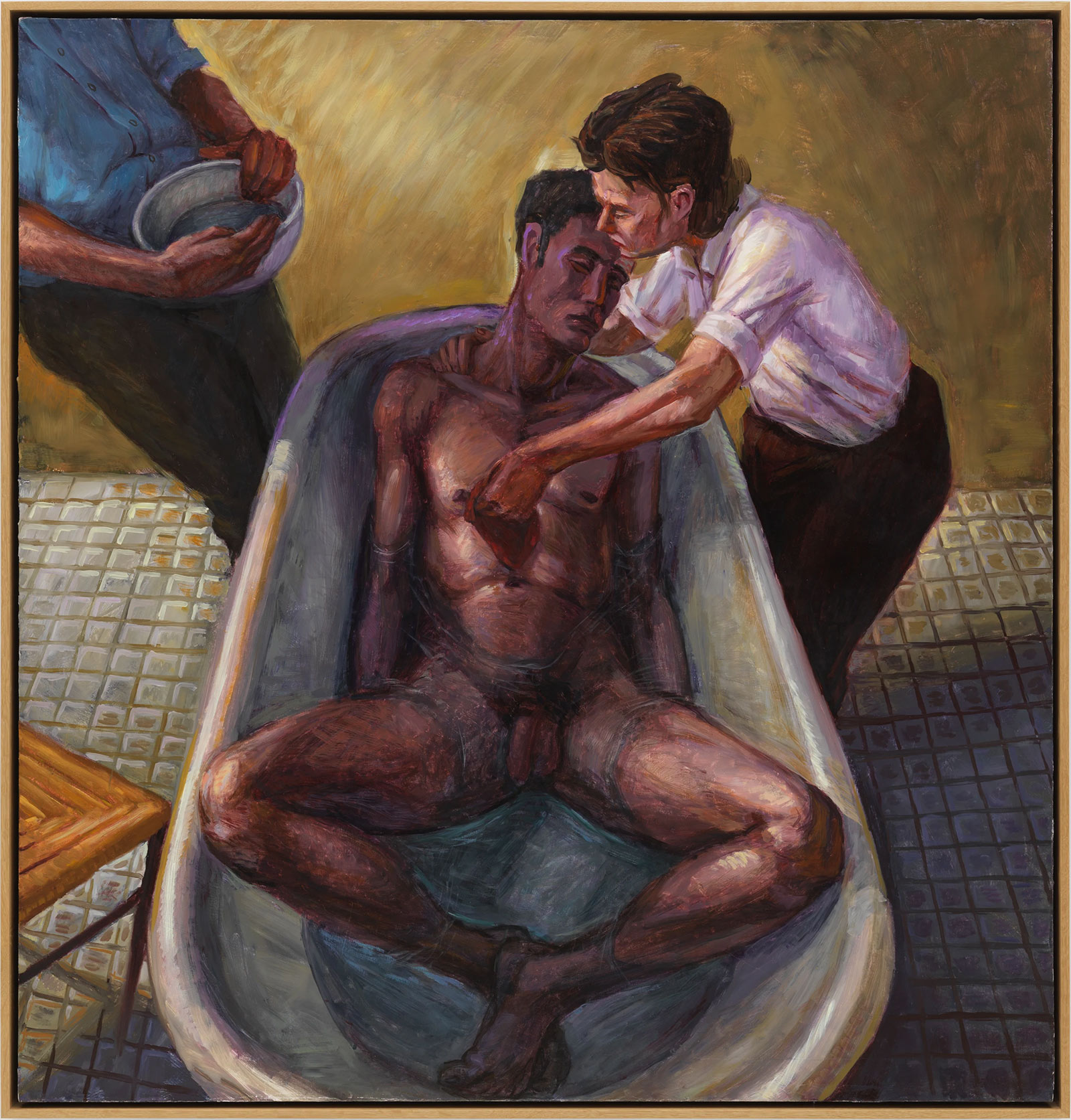

That this normality had to be hard fought for is further proved in the striking paintings of the late American artist Hugh Steers, who in his short career brilliantly painted the lives of his young lovers and friends and, by doing so, made his oeuvre a poignant chronicle of the devastating AIDS period. Steers’s work made it possible for the new generation of LGBTQ artists, like the French painter Jean Claracq, to play with art history and the concept of desire in a new light and witty manner. The sculpture Monument combines elements traditionally associated with the female or male territory (a baking mold versus the football player) leaving space for interpretation.

BODY

PART II

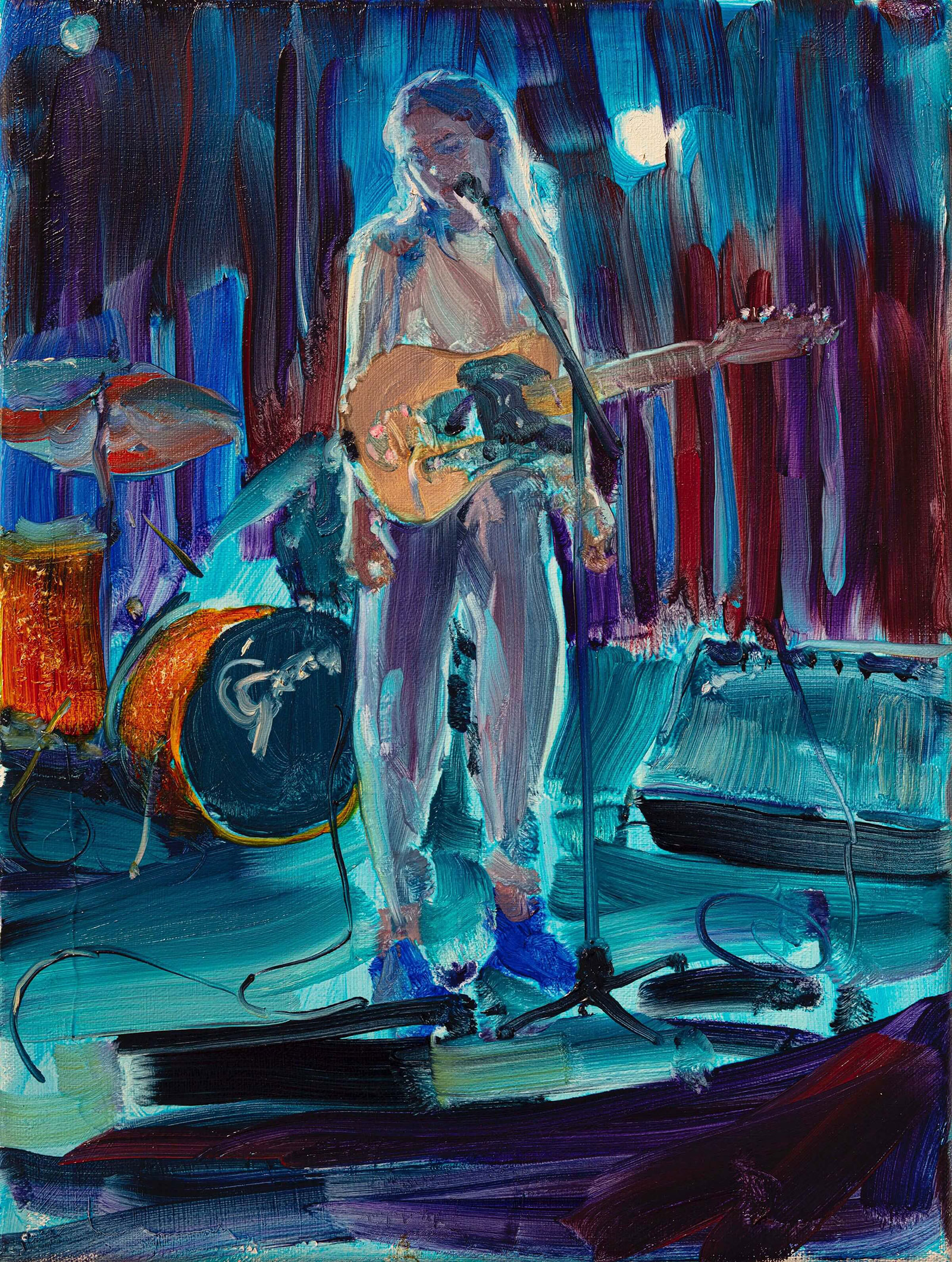

Section two highlights the process in which the female body has been reclaimed in the postwar period by women artists themselves. The current #metoo movement has given a new impulse to feministic approaches in art, resulting in a call for more visibility and for manifestation of the female body in different ways than before. Throughout art history the idealized female body used to be adored, often rendered as a supranatural being or as a muse to the male artist. The muse of the new generation’s artist Jenna Gribbon is her wife, the musician Mackenzie Scott, whom Gribbon depicts in a sensuous manner, but uncensored and unidealized. Comparable to Gribbon are the young Paulina Stasik and Agata Słowak, making art that aims to liberate women from the so-called ‘male gaze’, a normative control instrument that used to dictate how desirable women should be depicted and, consequently, how they should behave to be desired. These women are no longer here to please, but to make their art as they like, and live their lives as they wish, pointing at the same time to the still existing oppressive mechanisms, such as in Słowak’s sculpture related to abortion.

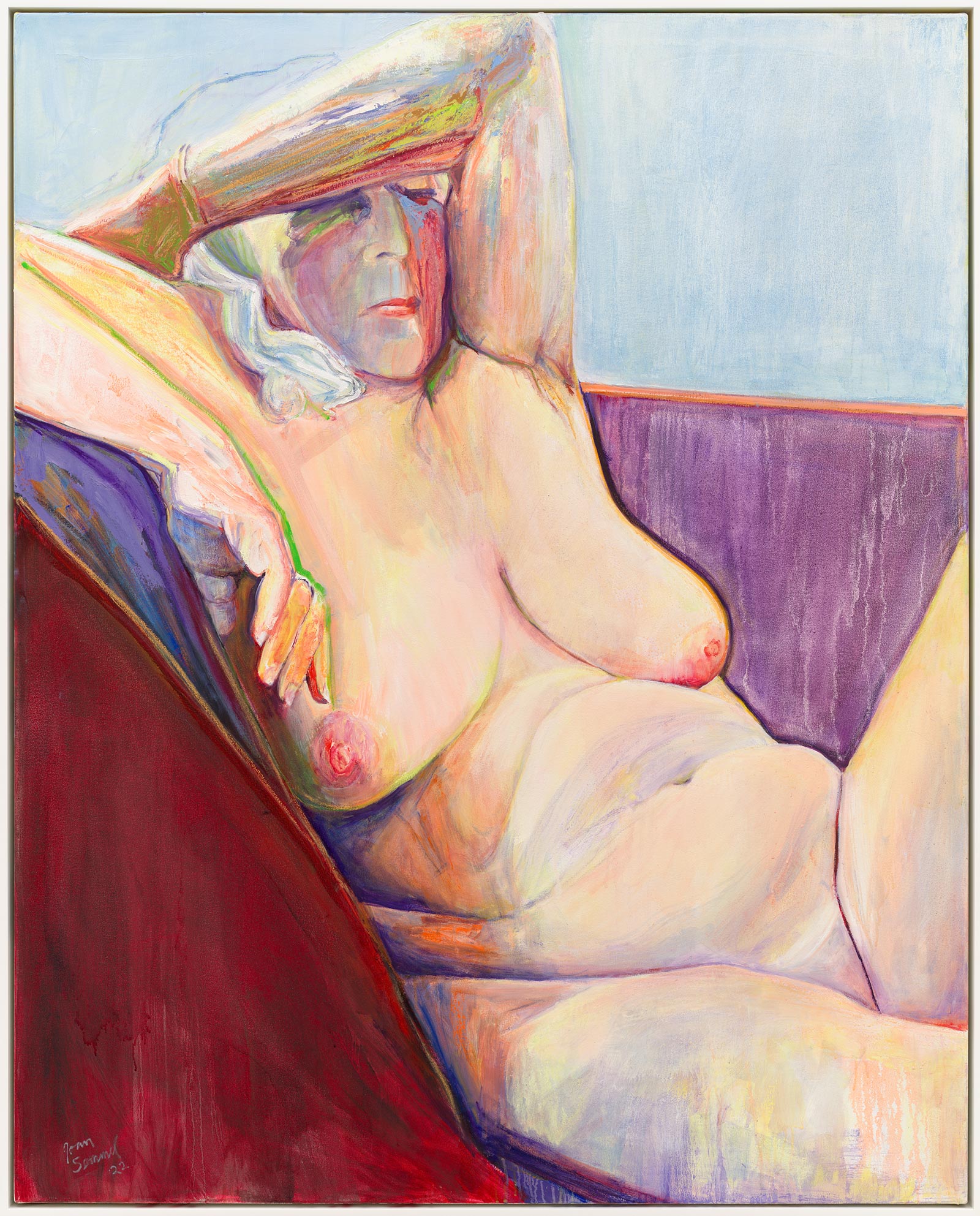

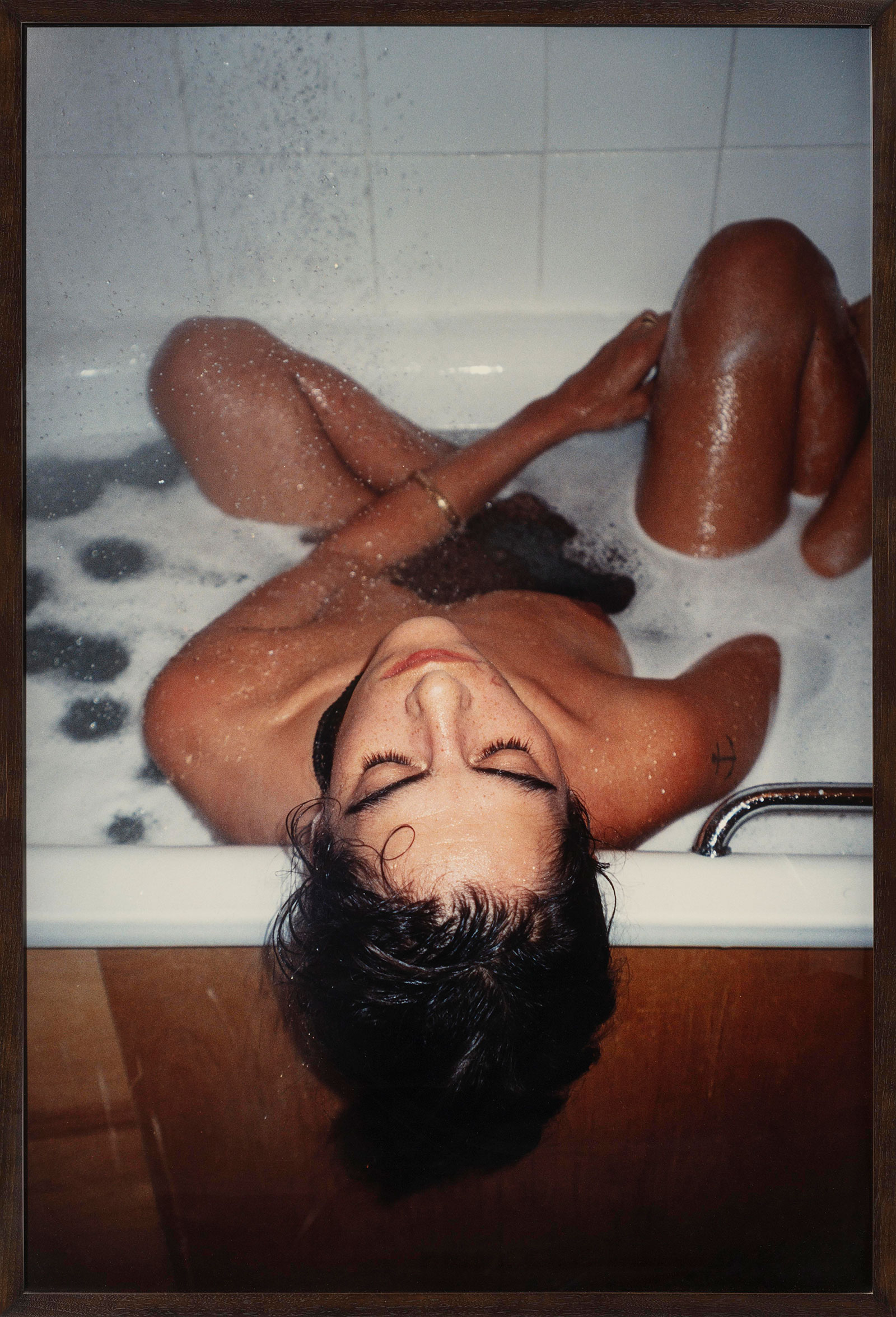

Three important postwar masters showcased in the exhibition have paved the way for these contemporary women artists. In the 1970s Joan Semmel started to paint herself nude as the protagonist of her works – without restrictions but also without idealization. Fearless and perseverant, Semmel has become a role model for many contemporary artists attempting to emancipate women from restrictive social expectations. A comparable attitude has been palpable in the highly personal oeuvre of the English artist Tracey Emin, who, peerlessly, exposed female beauty, and corporeal hopes and fears often in a shameless manner. Merciless in confronting big audiences with the oppressed female body, the Swiss artist Miriam Cahn uses her brilliant sense of color and delicate rendering of paint to antagonize the topics of her work, often related to violence and brutality.

The other role model, the late Alina Szapocznikow, was an important innovator of the artistic medium and materials in the 1960s. Szapocznikow experimented with unusual substances such as polythene, making casts of her own and others’ body parts, like in the work in the exhibition. These experiments led to opening up the art world for other materials and approaches, but also for the use of one’s own female body as the medium and subject of art.

Experimenting with new materials, like everyday waste and rubbish, was the English artist Phyllida Barlow, who is known for her ambitious robust sculptures claiming the space. This great artist who was ‘rediscovered’ by the international art world only in 2010, when she was 66 years old, became celebrated during her last years as one of the leading postwar Western sculptors. The process of rediscovery and revaluation of overlooked artists who led to transformations of the Western artistic canon, has been one of the most defining movements in the art world in the new millennium.

BODY

PART III

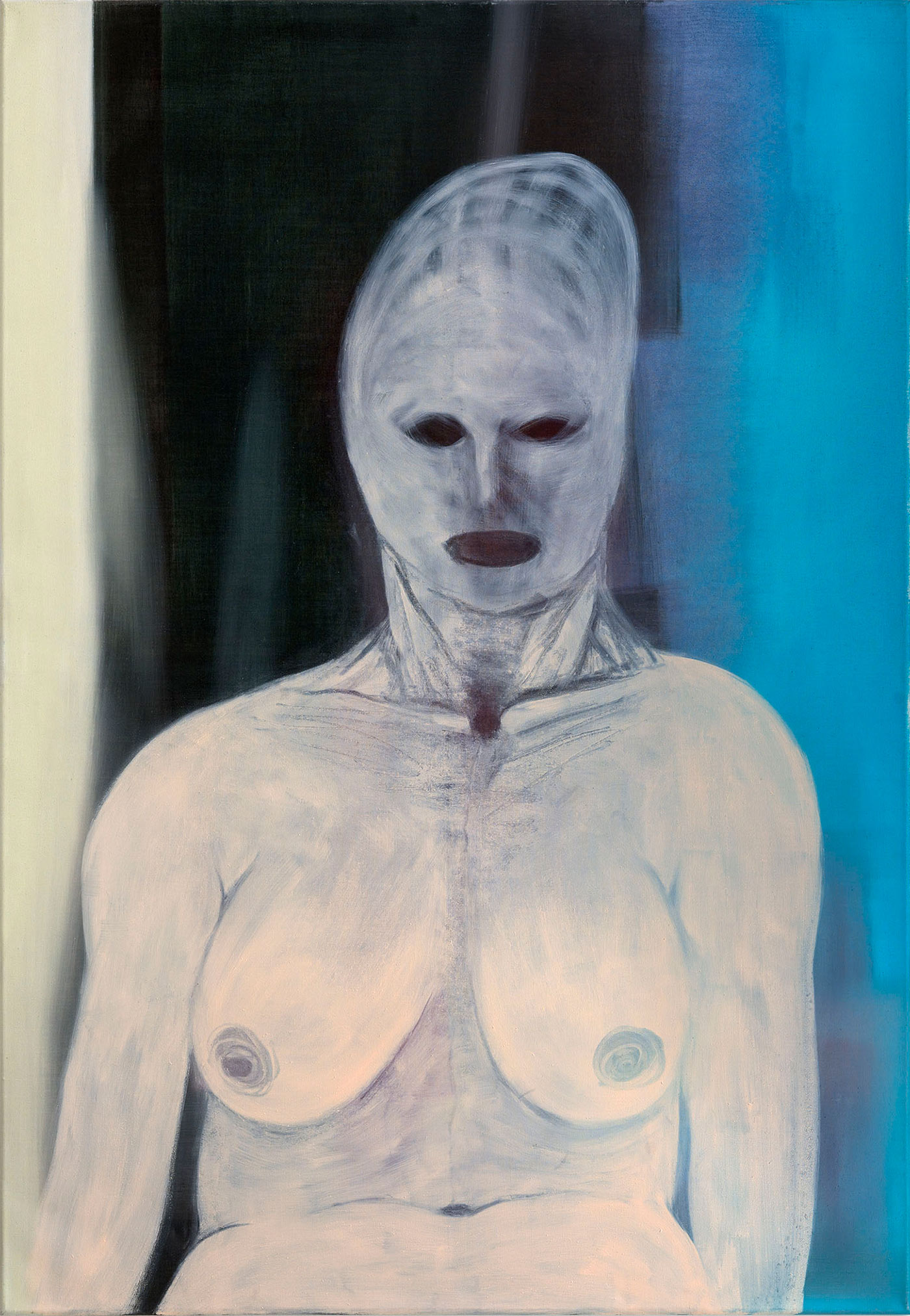

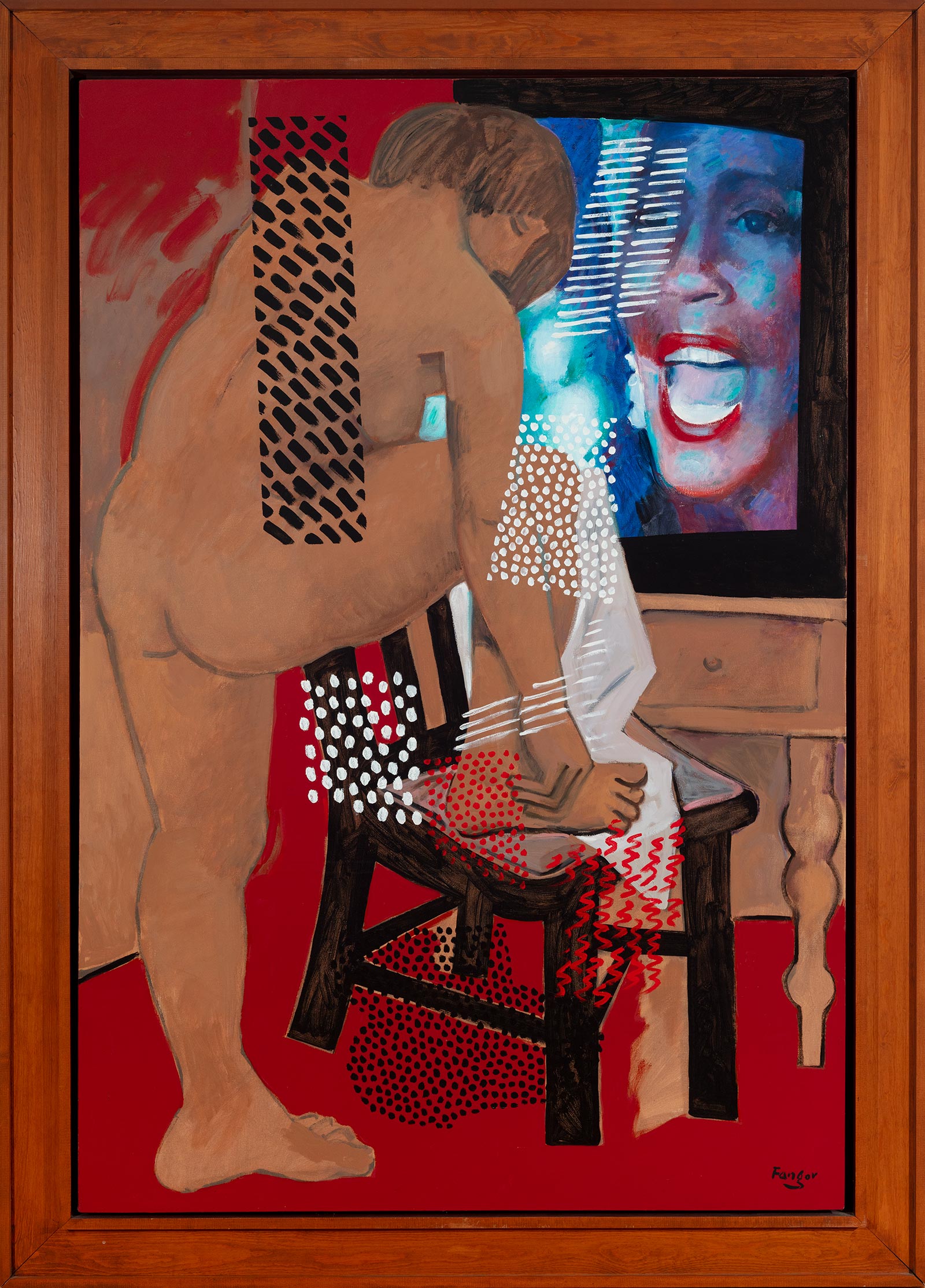

Section three explores the representation of the body in relation to the art-historical tradition and art-theoretical concepts. Almost every artist begins with drawing andpainting nudes, making the body the field where you train your skills and develop the feeling of line and shape. The body as art historical material plays a prominent role in the works by the virtuoso English painter George Rouy, whose nudes border on abstraction with his figures dissolving in powerful brushstrokes. The Czech artist Vojtěch Kovařík digs even deeper into art history, and models his bodies on archaic sculptures recalling the reduction of forms and perceived perfection of ancient times. The Austrian painter Martha Jungwirth explores the rich and multifaceted tradition of gestural abstraction, in which the body is present and palpable although not explicitly recognizable. Her firm expressionistic brushstrokes, the size of the works and the traces of figure place the Jungwirth oeuvre in the long tradition of artists asking questions about the representation – often expressed in the opposite between abstraction and figuration. A different question about the representation is asked by the German master Georg Baselitz, who has been painting the reversed figure since the end of the 1960s, provoking the existing order and our ways of seeing. His signature painting, the naked reverse figure suspended in the air, was an attempt to liberate the content from what it stands for in order to concentrate on its painterly qualities. The long tradition of fragmented and reshuffled body is addressed here by another German artist, Daniel Richter, who gives the color and the line the prominent roles while quoting from different sources such as pop culture, historical documents, and mass media.

SOCIAL NETWORK

PART I

The main topic taken up in section one is the Other, embodied by the immigrant or a person of ‘other’ ethnic or cultural background. Aware of their own positions, the artists dissect and analyze the problem of societal exclusion and inclusion, and the mechanisms of these processes without offering moral judgements. The negotiation of social positions is depicted in the fresco by the British duo Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings, showing the social fabric in contemporary cities where many interests collide, and where the social space is not taken for granted but fluid.

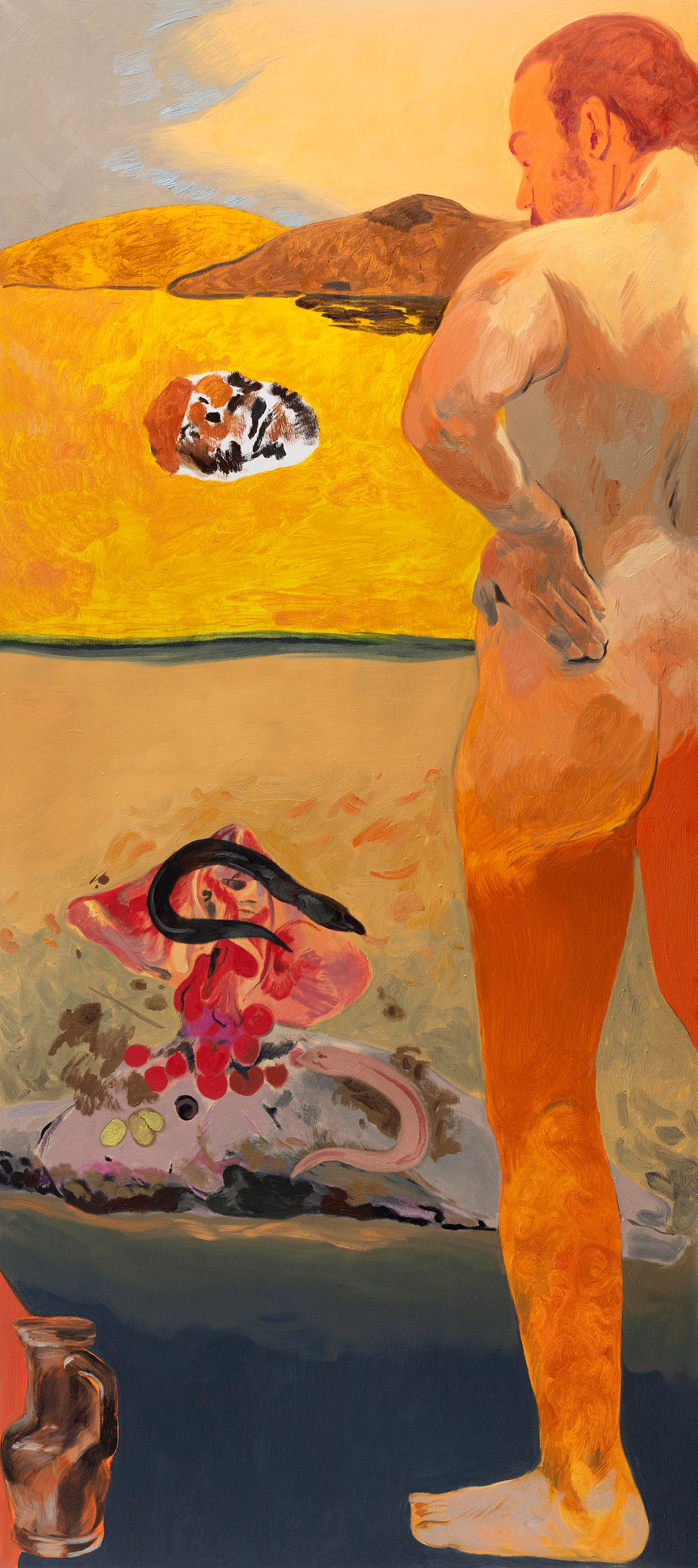

The section gives further space to several outstanding artists with migration backgrounds, who reflect on their own position in Western societies as often being Us and Them at the same time. The fear of the unknown Other can be found in works by the Chinese-born French artist Xie Lei. An excellent painter anchored in Western art history, Lei’s dreamy works are imbued with ambiguity suggesting latent violence and ecstasy.

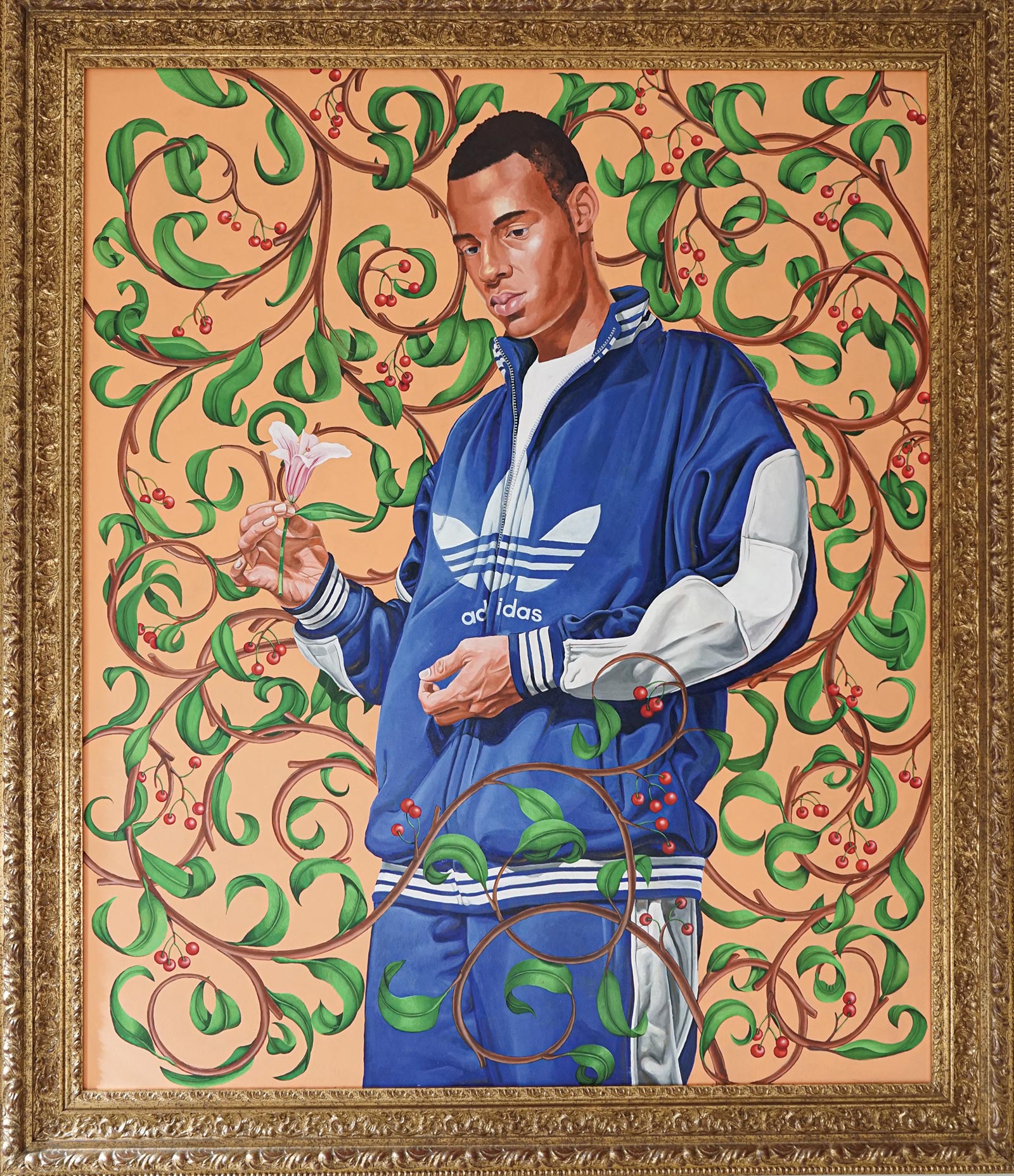

The Algerian-born, Paris-based Dhewadi Hadjab uses the tradition of the Western grand painting to stage scenes in which the protagonist is placed in an uneasy, tense, and physically challenging situation. Effortlessly referencing 17th-century Old Masters, Hadjab depicts his young, casually dressed heroes trying to somehow find the balance in a mysterious setting. From a similar background is the artist Mohamed Bourouissa, whose striking sculpture dominates the gallery space. A young man in a characteristic urban hoodie, looms over a pile of debris twisting the idea of a triumphant equestrian. As an insider, Bourouissa investigates life of suburban communities with their own rituals and norms, asking the question, how is identity being created and perceived?

The Pakistani-born French artist Aïcha Khorchid uses her personal immigrant experiences to reflect on the human condition in the broadest sense of this term. Having grown up in a French foster family in Normandy, where she lived through all kinds of abuse mixed with moments of happiness, Khorchid digests her childhood by making emotionally charged large tableaux with people that inhabited that world. Also addressing the subject of displacement and memory is Petrit Halilaj of Kosovo-origin. Confronted with the war traumas of European recent history Halilaj seeks in his works symbols and sings that are universally readable, such as the series of children drawings found on school banks in Balkan transformed into bronze sculptures.

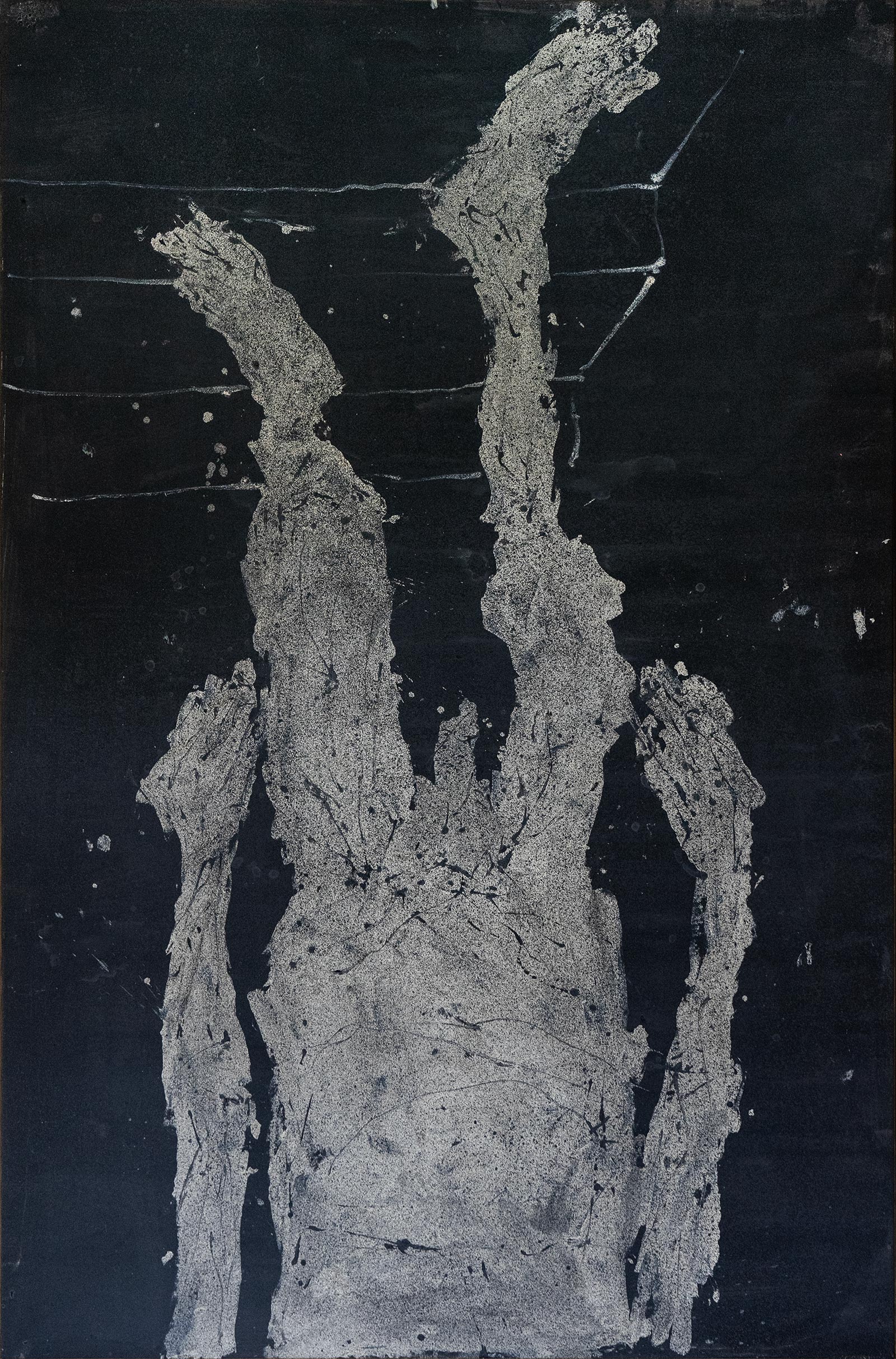

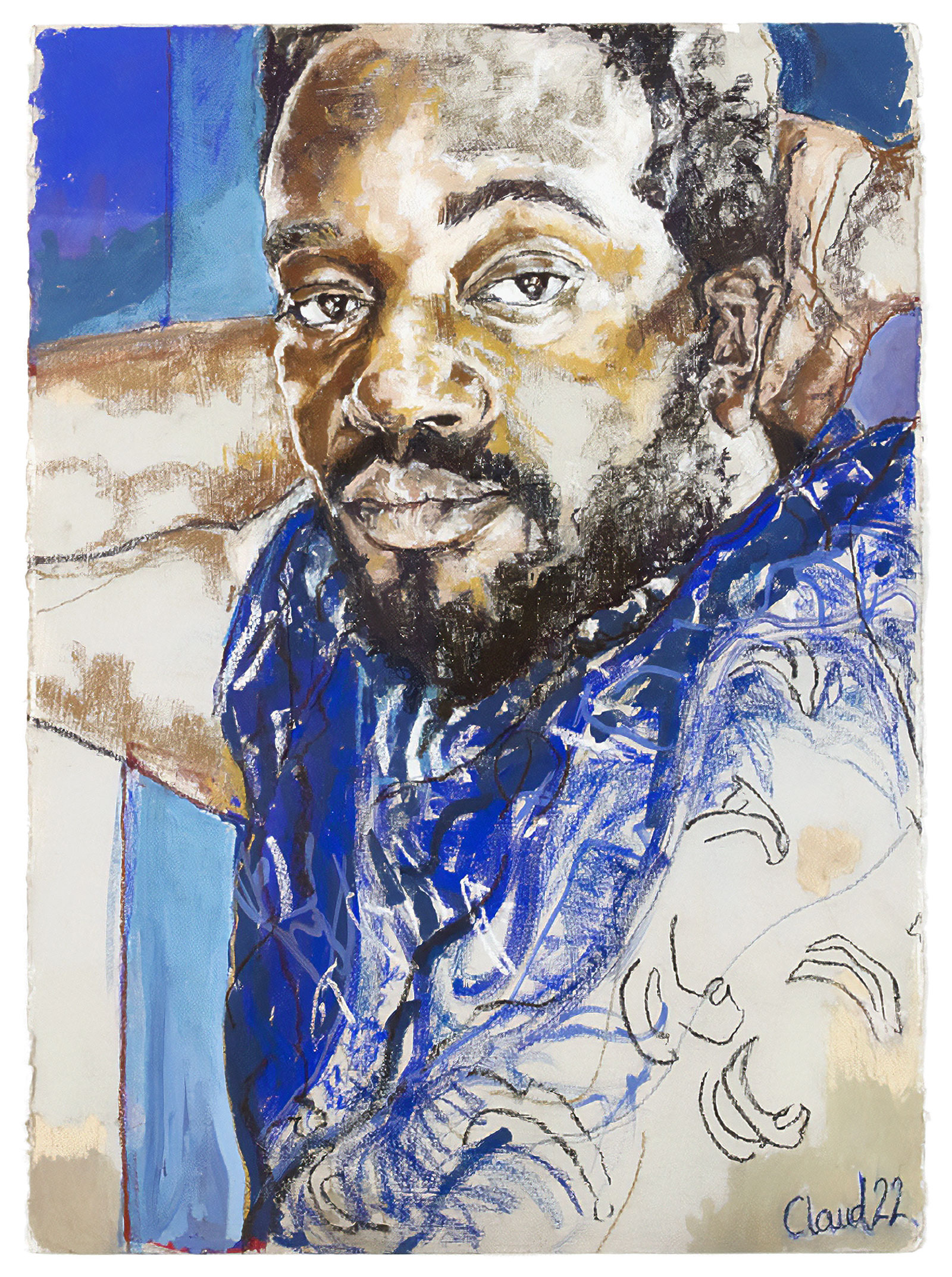

Kaifan Wang’s ever evolving, but already characteristic, style displays his profound skills in Chinese calligraphy in dialogue with the tradition of Western abstract expressionism. In her enigmatic portraits of an undefined assembly of people, the German artist Melike Kara, of Kurdish descent, points at social hierarchies and the danger of losing one’s individuality in a group.

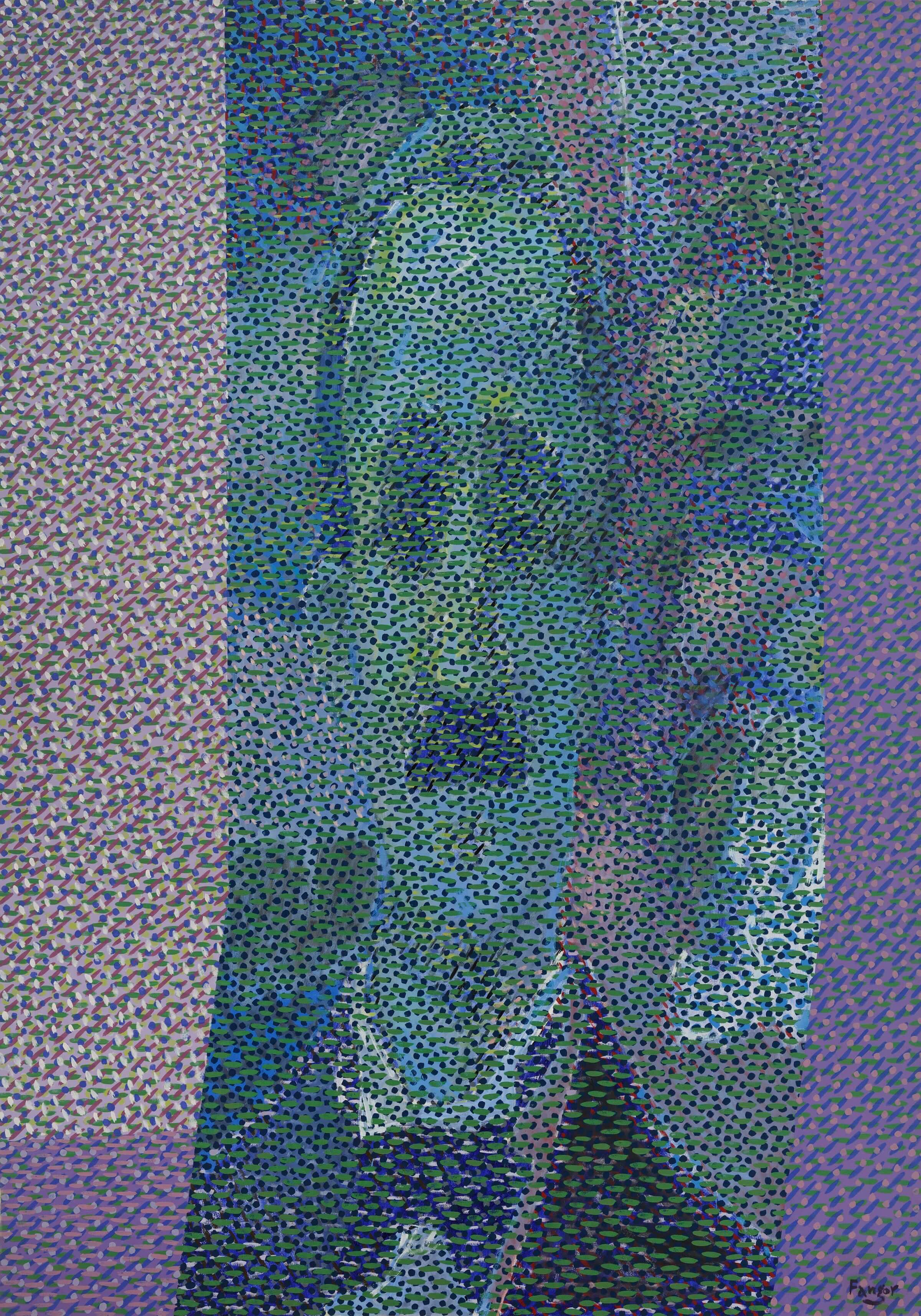

Nour Jaouda explores the idea of nature as the carrier of memory, imbued with personal and collective meanings. Born In Libya, and now living between Cairo and London, Jaouda creates environments that play with a socio-cultural rooted and rootless existence. She arranges her tapestries, made from dyed canvasses, in a relief-like manner so that they function as a witness to change, which is often denied by memory.