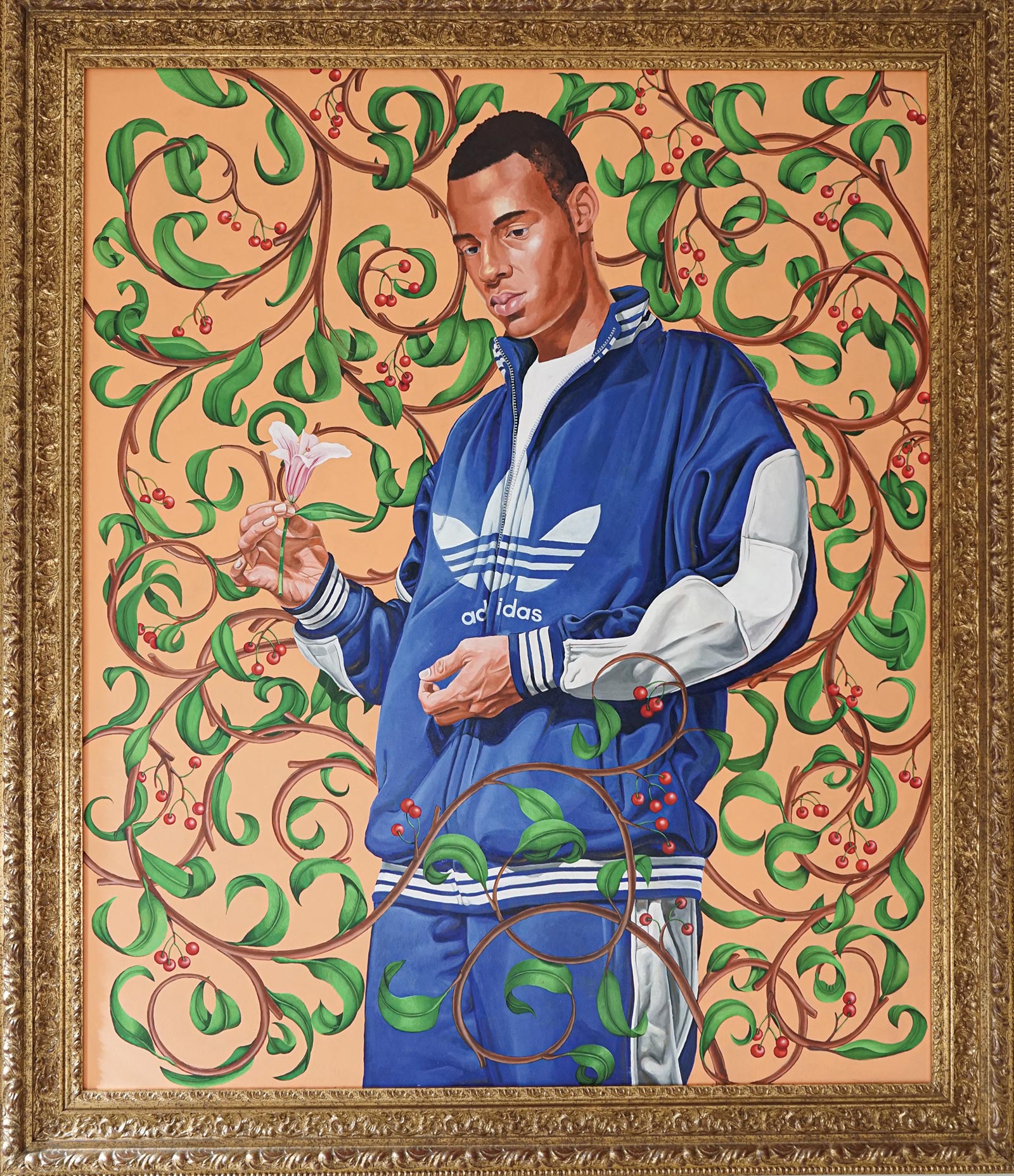

Kehinde Wiley

Passing/Posing (Lady Innes)

Oil on canvas

213.4 x 183 cm

2005

Kehinde Wiley (American, born in 1977) helped give new life and relevance to the traditional art form of the historical portrait. Throughout the centuries, portraiture has been used not only to depict a subject’s potentially true image, but also to transmit information about status and wealth of the depicted figure, and, by doing so, show intricate dynamics of power in a given society. Equally important to capturing the character of the sitter was to glorify them and their time. Wiley uses the associations that we have with historical portraits to elevate the position of common urban people of color, by including them in a world in which they had been invisible for a long time and seldom played a central role. Thanks to the familiar art-historical setting, Wiley makes his protagonists equal to kings, aristocrats, and saints.

Passing/Posing is the title of the series of paintings that refers to Wiley’s process of making his works: he would observe people in passing in the street and approach some of them to pose for him in his studio. If the stranger agreed, they would choose a pose that they liked from art historical books; then Wiley would photograph them and use the photograph as the basis for his painting. The encounter with the ‘sitter’ was very short and lasted a maximum 30 minutes, as opposed to the days or weeks of posing for a portrait artist in the past. Wiley’s ‘sitter’ remains anonymous to the public to confront the traditional idea of the glorified one individual. Once the pose was chosen, Wiley himself would then choose the patterned, ornamented background.

The second part of each painting’s title (Lady Innes) points at the existing painting from which Wiley’s sitter took his pose: Thomas Gainsborough’s Sarah, Lady Innes (1757), now in the Frick Collection in NYC, portrays a fashionable, aristocratic woman in her opulent blue and white dress with a flower between her fingers. Blue and white are also the colors of the Adidas tracksuit that the young African American man wears, which equates this everyday urban clothing to the 18th-century upper-class dress, and suggests that being fashionable has always been a group code. Caught in his thoughts, Wiley’s protagonist holds a flower in his fingers, exactly as the Lady Innes does, communicating, however, different politics of visibility in today’s world.